On the bonds of fellowship: Can Am 250 2017

Wherever I went in this race, I heard this: 'she started with only 10 dogs.' I heard it when I would arrive at checkpoints, I heard it when we would be visited by the vet team, and I heard it directly when another musher said to me 'you're crazy.'

But, none of them knew these 10 dogs.

The Can Am is a true test of teamwork, always. The terrain is relentless, and this year the trails were hard and fast and icy, so much so that I ran with chains under my runners for the first 10 miles after we left the railroad grade in the first leg of the race. We crossed open glassy windy lakes, the sled drifting sideways in the wind as Wembley and Ia dug in with their toes to keep us on track. We ran down wide plowed ice roads, and up so many hills, scaling ridgelines. I broke yet another sled in the first 50 miles of the race and drove it with a broken stanchion for the remainder, as I managed to break the one thing that couldn't really be field repaired (although I did like Race Marshal Don Hibb's suggestion of finding a piece of tree and bending myself a new piece of lashing). All, with these 10 dogs.

The Can Am 250 celebrated its 25th year this year, and for the first time in its 25 years, the trail was rerouted due to open water and lack of snow on plowed roads. The entire race was restructured, all in the two days before. As mushers, we found out on Friday. The race started Saturday.

The chaos of the volunteers was palpable. Not many people knew the full story, rumors were flying about where or what kind of checkpoints there would be, and whether dogs would be trucked to get from the trails to the checkpoints. On the drive to Fort Kent, once I heard the news, I was even strategizing potentially breaking up multiple 60 or 70 mile runs with camping on the trail. When I saw the map, and the mileages, when we arrived at registration, the entire race was different. The entire middle of the race was gutted, the long descent climb out of Rocky Brook to Maibec to Allagash. Gone.

The streamlined checklist of the musher’s meeting devolved into exclamations from the floor, different people trying to answer the same question, and so many questions that the answers were made up on the spot. I sat in the back of the room, asked questions of the trail volunteers next to me to get a sense of how plowed the plowed roads were, and waited. The one question I had, which I didn’t ask but would later apply, was if they had decided the latest-out times for the new checkpoints.

The new race format was Portage-Portage-Allagash-Finish. Knowing that we had done so many camping runs at the same exact spot, returning and leaving from it over and over again, I knew it wasn’t going to be a big deal for me and the team to return to Portage a second time. In fact, I kind of liked the idea. And, honestly, I liked the mileage: 209 miles.

I didn’t intend to change my original plan, which was rests of 5-6 hours at each checkpoint. The longer rests were to keep the team’s speeds and spirits high, building in a positive experience for the younger dogs on the team and a fun experience for the older dogs. And, well, with only 10 dogs I wanted to make sure they stayed well-rested. It had been less than two weeks since the UP200.

Thus, Elissa and I quickly repacked the checkpoint bags, combining and cramming the coolers full of meat.

There are always a lot of unknowns in races, especially in Can Am as the trails are described sometimes in so much detail that they feel risky, or not enough detail to make sense. One person’s unplowed road, meaning it hasn’t been plowed recently, is another person’s plowed road if the unplowed snow has melted away. The trail is often laid out without understanding of the physics of a long string of dogs, with 90 degree turns off ungroomed snowbanks onto plowed roads. One just doesn’t know.

And, the sled, was a sled I was borrowing from a friend. It was a sled that had sat for a few years, and a sled that I had only driven twice before the race. The brake was a specialized design, that I called a ‘non-brake’, being a drag mat with three sets of carbide tips, instead of the classic bar brake/ drag mat combo. I was having a hard time re-learning how to stand, steer, and slow down the team using that brake. It was a sturdy sled, but it still felt unknown.

Last year at the UP200, I finally learned the essence of the phrase ‘run your own race, run your own team.’ Since then, I feel even more honed in on the dogs in the team, and only the dogs in the team. It is a zeroing in on the immediate in front of me, not worrying about teams that might be ahead of me or behind me, or when or how or if we’d reach a checkpoint.

Thus, combined, there were a lot of things to distract me, to stress me out, the unknowns were so amplified. Sleds, trails, wind and cold.

I was so thankful for these 10 dogs.

At the start, Wembley and Hyside were in lead. I trusted them completely. This was Wembley's fourth Can Am start chute, and Hyside has led so many start lines. These dogs are professionals.

Hyside. All eyes forward. Wembley probably looking for someone to bark at.

Leaving Fort Kent at the start, the railroad grade snowmobile trail we start on was sandy icy snow. I saw Ashley, who had left in the position in front of me, and knew it was a ridiculous idea to pass her this early in the race, since she would just pass me anyways, so I slowed the team down until she left my sight. Denis passed me, as I hoped and told him he would. After 7 miles, we reached the true start of the Can Am trail, and the true finding of what the rest of the race would be like.

We swung through the skinny section in the woods, and then slid into the wide road with the uphill. The trail had already been run on by the 100 mile teams and the 30 mile teams, and any traction on that trail had been shaved away. Not confident on the sled I was driving, it wasn’t long before we started sliding down the slight camber in the snow, and off into the trees. I slowed and stopped the dogs, and we made it back to the centerline.

Not long after that section, after crossing a glassy lake, the trail became moguled, with long downhills. Still having a hard time steering the new-to-me sled, I said ‘f*ck this,’ and stopped the team, set the snowhooks, and in a few seconds had run the chains I had tied to the bed of the sled around the runners. For me, in that moment and absolutely at that point, the trail had become about maintaining a healthy and strong dog team. Nothing else mattered.

With the chains in place, controlling the sled and the speed became comfortable. They kept a happy 9-10 MPH, and I was happier with the twists, turns, and occasional pothole. After about 10 miles, we left the 30 mile trail, and started hitting some longer uphills. I stopped and put the chains away, and we had an unremarkable rest of the run to Portage.

Well, almost unremarkable.

In this first leg of a race, we all end up passing, catching or being passed by teams often, throughout the entire length of the 70 miles. About halfway through the run, I was in a group with Marie Eve ahead, and Gilles behind. I watched Marie-Eve stop her sled, and hop it around a turn. I slowed down so I wouldn’t overtake her, and in slowing down the sled, kept it tooooo sloooooow….and then pivoted the sled directly into a tree. Head on.

I’ve hit trees before. I’ve hit rocks before. I’ve had my sled jammed in-between tree stumps and gate posts. This was no big deal. I set the snowhooks, and was standing with my snubline in my hand, looking for a tree to tie off too so I could pull the sled back away from the tree, and not have to rely solely on my snowhooks, when Giles came along.

In a rapid few seconds, chattering to me in what I think was English, Giles performed what I was going to do with a tree, pulling back on the line while I stood on the brake. The team was released, and we continued on our way. I noted the broken brushbow, and that the bridle was now loose, adding to the difficult of steering. Just something to mac-gyver the next time we hit a wide road and a snack break.

The unplowed roads on this trail were, after all, plowed ice roads. It was on these sections that I learned to love the non-brake on the sled, the three rows of carbide studs offering more control than a drag mat and smoother movement than the brake bar. Ia and Wembley were in lead, Ia leading so intelligently and smartly, her gift to the team in these long runs.

On one of these sections, I noticed that I had also broken the connection in the front stanchion when I hit the tree. Having just broken a sled in the UP200, and knowing that the remaining sections of trail wouldn’t be technical, I knew we would get to Portage fine, and that there would be a lot of people with opinions on how to fix the sled.

Going on and off these plowed roads can sometimes be less than straightforward. The markers are small and not always well placed, and the trail you turn into can be narrow. On one of those sections, we came upon Becki’s team doing 180s in the plowed road, her screaming at them to try to direct them as her sled bent in half as her team flailed around her. I told her to hold still, gave Wembley and Ia the ‘haw’ to turn across the road and into the narrow trail, and they executed it flawlessly. I stopped and set my hooks, and waited to make sure Becki’s leaders followed suit.

Throughout the year, I have been training the team for what I call ‘resilience’. One part of that was, indeed, turning across wide snowmobile trails onto a narrow ungroomed ATV trail. We did that in training because I found it fun, different, and a change of pace, and also a way to get away from the snowmobile traffic. It was amazing to see that training come into play in this race.

The remainder of the run to Portage was quiet. We had one gnarly plowed road left to execute, shooting through a classic Can Am narrow break/ 90 degree turn snowbank (me somehow landing on my behind, but still holding onto the sled) and then taking a fast right hand turn off the plowed road and up a steep hill. We were surrounded by other mushers, Jaye and Becki and Marie-Eve, but I stopped a lot to let them get ahead of us, so I could enjoy the evening and the long slow downhill to Portage, one of my favorite 20 miles of the entire race.

Crossing Portage Lake heralds the end of that long 70 mile run. This year, instead of the long run across the lake, we crossed a narrow end. Wembley and Ia were leading well, so inbetween bumpy icy jolts, I managed to get out my camera to capture the sunset. The wind was moderate. The glassy ice was so many colors in that setting sun. We. Felt. Great.

Pulling into Portage, we were greeted by volunteers we knew well, from so many checkpoints. It was going to be a different kind of race.

Portage was a cold and windy place, temperatures somewhere around the single digits but the blowing wind making it that much more colder. Booties I put on the ground blew away. I used the sled as a windbreak for gear, and put every ounce of warming gear I had onto all of the dogs. In the rush of packing, somehow I had mislabeled bags, and the checkpoint bag I opened was the checkpoint bag for the second checkpoint, missing the warming shoulder vests that Ia and Ariel received at every checkpoint to help them rest well. I did what I could, using excess straw to build windbreaks, and wrapping Hilde in a burrito of wool blankets, but some dogs weren’t resting well. Some dogs didn’t seem to mind a thing, such as Wembley, Hyside, Inferno, Hawkeye and Oriana.

I asked the opinion of everyone about the sled, and what to do about it. Knowing that the next section was non technical, a simple smooth 40 miles of snowmachine trail, I wasn’t too worried. I braced the stanchion, and would keep an eye on it.

The next leg was unremarkable, save for the opportunity to pass all the mushers head on. It was on that leg that I knew that Jaye Foucher was having a great run, seeing her team charge at me. I was so so so happy for her. I struggled to stay awake, Wembley and Hyside in lead leaving me very little to do. It also grew cold, and I wished I had thrown some hand warmers into my beaver mitts.

Back at Portage 2, in the rising sun, it felt strange. The teams were starting to get spread out, the Canadians readying to leave when I was still bedding down the dogs. The day seemed too bright, and the wind was still blowing. Scott Giroux, one of the super volunteers who manages the Syl-Ver dog yard, pointed out that the stanchion I broke was not structural, but instead would only affect steering. The bed of the sled, the other stanchions, and more were doing the work of holding the sled together. I would be fine.

Readying to leave Portage 2, to head to Allagash, I looked the team over. No one had eaten well, and I called the vets over to potentially drop Oriana, as she was not eating well and as a young dog, I didn’t want that to be a negative experience in long races. However, by the time the vets came over, Oriana was eating like a champ, but Ariel was displaying some non-identifable soreness and Ia had developed a shoulder cramp I couldn’t work her out of. Everyone else seemed great, Nibbler rising to cheer us out. It felt strange to be leaving Portage in daylight, it felt stranger to be heading to Allagash so early, but the 8 dogs in the team and I were ready.

Until, Hyside's gait was different immediately. I stopped the team, and sat down on the trail in the sunshine with the wagging happy dogs, and found a wrist injury on him. I knew we had to go back to the checkpoint, I was not carrying Hyside up all the hills to Allagash, and we were only a mile or two from Portage. I cut them all loose, turned the sled around, played with them and made them happy, and called them to me and drove back to the checkpoint. I thought my race was over. When I got back to the checkpoint, I couldn't quite say the words scratch.

When the crew brought me through the dogyard at the checkpoint, to return me to my truck, a flash of inspiration and hope returned. 'No, wait.' I said 'Bring me back to the dog yard, bring me to my straw.' There was a possibility that if we treated Hyside, he could get back on the trail.

Everyone at that checkpoint did everything they could to get us back on the trail: the managers who figured out what rules applied (how long could I stay? Could I access all my checkpoint bags?) and the vets who coached me through the options, including sitting and helping me hold Hyside still while we iced his arm. Remy Leduc said, as we sat in the sun and cared for our teams, ‘can your dogs chase? You can follow me and we can go together.’ I asked him if this was legal, and he said ‘of course it is, we just can’t tie our teams together.’

I came inside, and sat with Elissa, working through the options. I felt not-so-sure about our ability to continue without Hyside, leaving only Wembley as a leader. Hilde was still in the team, but she would not lead with girls.

Then, Elissa asked, ‘What about Inferno?’

Inferno is a young dog, a yearling. Elissa got to know him last year, as he was transported to the race for me by Laura Neese, and Elissa cared for him when I was on the trail. Inferno became famous during that time, as he destroyed and busted out of the box, and ran around Portage, chasing snowmobiles. Inferno comes from a long line of leaders, his mother Salt a lead dog before age 1, and going further back to his great grandmother Lily, who lead the Yukon Quest as a yearling, her very first time in lead.

But all of these things did not come to mind, for me, when I thought about Inferno. I thought of his immaturity and slight goofiness sometimes, and of the few times I’ve put him in lead, where he showed promise, but not something reliable. I was worried about exploding his head in a tough run, like forcing him to lead for 100 miles. But, then, I remembered watching him in the UP200, where he seemed to get stronger and more confident as the race went on.

With Remy, and with Elissa, and with the others at the checkpoint, we had a plan.

I dropped Hyside, whose wrist was still swollen, and headed out onto the trail with Wembley and Inferno in lead. Paul Roy, one of Remy’s friends, was waiting on the trail and caught a photo of the team leaving. It was one last moment to cheer us out and on. We were 7 dogs, 1 musher, and a broken sled facing 50 tough miles to Allagash. I needed that cheer.

The slow climb out of Portage was banked with beautiful setting sun. Inferno was running beautifully with Wembley, and she seemed happy. Oriana and Nibbler were right behind the leaders, and they displayed so much patience when Inferno would lose focus and slow down, leading to tangles that they would somehow leap their way out of. Foreman and Hilde were in wheel, Hawkeye solo. They were all working as a team.

As sun gave way to darkness, and we started climbing ridgelines at mile 20-25 or so, Inferno decided he was done. Knowing better than to force dogs to do anything, and also knowing better than to stop or slow down too much, I kept them moving, and coaxed other dogs into the front with Wembley. I walked up and down the team, tired. This was not the run I wanted, a complex and confusing run to Allagash, in the darkness and cold.

Remy’s headlight appeared not long after, coming up with his puppy team. I said I needed to follow him for awhile, and helped his team pass. Sure enough, Inferno perked up and we chased him most of the way to Allagash, Remy stopping to wait for us when something happened and we fell behind. (How on earth did he know when he had lost us? I later found out that Remy knew that we had fallen behind when his young dogs suddenly became more focused and were running better.)

The last 15 miles to Allagash were a long mostly-downhill iced road. Wembley somehow knew were she was, and her speed and focus picked up. I was drifting in and out of sleep, waking to find the sled close to Remy’s. I eventually let the team pass, Wembley and Inferno leading us into Allagash at last. Remy and I talked after bedding down our teams, I thanked him for helping us get here, and we talked about the run.

Allagash always feels like a bright happy party. The diner is lit up with so many lights on the outside, and the teams are spaced in a way that they can rest well. The volunteers and staff are smiling, a lot. It is a short walk from the dog yard to the diner, and there is so much warmth and cheer in that little building. And, also, the sleeping quarters for the mushers are quiet warm bunks. Elissa was there, as were Paul and Kat, and they all greeted me with big big big hugs. ‘You did it’ they said. ‘We did it!’ I said.

As always, I knew if we got to Allagash, we would get to the finish.

I had intended to rest for 6 hours, but that rest became 8, as I just was moving slow myself, having expended a lot of energy on the hills to Allagash. Inferno and Wembley stood right up when I went to check on the dogs, and everyone ate. They felt recharged and ready. I was worried a bit about Foreman, his wrists were sore and his appetite was never great after Portage. But he ate ok, and he moved well. In this race in particular, I don’t like taking ‘iffy’ dogs, because it is not fun going up and down those hills with a dog in the bag. Nor, does it feel quite right coming into a finish line with a dog in the bag, as I did with at the UP200.

I knew the trail to the finish would be doable. I knew we would have to climb out at first, but thanks to Amy Dionne leaving right after us, we had someone to chase when she passed us. I knew the remaining trail well, it being burned into my brain from the runs before. Rolling hills, some steep climbs, and a heating sun were still to come.

As I had expected, but not hoped, Inferno declared he was done, again, at mile 20. I shuffled dogs around, figuring out who would run with Wembley. Nibbler carried us for a short while, Oriana not far at all, and as a last-ditch effort I put Foreman up there. Foreman had led before for about 100 yards in a training run, and he did well enough in that training run, and Wembley was pleased wit his company, that I thought it would be worth a try again. At least, Foreman had more maturity than Inferno.

With a shortened-up tug, Foreman was slightly behind Wembley, so he had someone to follow. Wembley was thrilled with Foreman, and they moved us slowly but surely in the direction of Fort Kent. I remembered something that my friend Matt Schmidt had said about his Beargrease run, which was he would know they were moving slowly, but even slowly, that they were moving well.

When we reached the last 10 miles, Foreman was clearly done helping. Knowing that Wembley would know where she was, I put Inferno back up with her, still keeping the slightly shortened tug for him. He zipped in line. We kept going.

Wembley sure as hell knew where she was going. She jerked the team forward when we stopped. She guided us flawlessly through the open fields, even when Inferno would take us in a weirdo direction. She corrected turns when Inferno would try to take us down the plowed road instead of right across it. I trusted her completely.

There was still one last trail hurdle, that came unexpectedly. The trail curved to the right through the trees, and Wembley hesitated and then decided to go straight instead. I tried to see around into what was up there, and saw only an open pit of undermined snow, open water and mud. I saw no trail markers, and I saw no runner tracks. But, from my best guess, through the crevasse and the mud was the trail. I gee’d Wembley out of the woods and towards and into the big hole.

Trusting Wembley, but not the giant sled I had already broken, I set the hooks and used my snubline to belay the sled up that section of trail. The dogs were patient and willing, and we made it through, but not without the sled tipping sideways and me finally and at long last breaking the other stanchion piece on the opposite side.

I stopped not long after that to pull the snubline back in, and to thank the dogs left on the team. Nibbler was impatient and screaming to go, knowing exactly also where she was as well. The sun was so bright. I slowed the team down to enjoy these last few moments on the trail, sliding downhill with an exhale.

We came sliding into the finish, and Inferno tried to take us into the parking lot instead of the finish line. I could hear ‘GEE GEE’ being screamed at me from the finish line, and Stephane Duplessis ran out to help direct the team, but I smiled as I knew that once the team stopped taking the turn, that Wembley would fix it. The video of the finish shows that moment after she did, with me waving to Stephane as a thank you.

The smiles we all had at that finish were unlike the smiles at any of our other race finishes. I smiled because we were surrounded by so many friends, so many mushers, so many congratulations and thank yous and big bear hugs. Stephane stared so proudly at Oriana, the girl he reluctantly sold to me two years ago. Everyone laughed at Nibbler, leaping and ready to go again, and Wembley as she barked at everyone, her energy undiminished and unchanged. The dogs looked like they could keep going. I felt like I could keep going. It was sunny and warm, and we lingered in the finish line.

This race was about every dog on this team. About Ia who led us into Portage, confident on all the wide iced roads, and Ariel who drove and drove and cheered. About Hyside, with his steady and even pace and massive heart. About Hawkeye who was a steady and strong invisible member of the team, and Hilde who ran next to him the entire time, screaming with intensity when we left checkpoints. About Foreman who rose to lead for exactly 10 miles in the last leg even though he absolutely did not want to. About Oriana Fallaci, a yearling youngster who remained focused in point, even when the leaders would create constant tangles. About Nibbler, who was just a spark of energy in a harness, snapping forward every time I whispered it was time to go again and leaping and screaming when we waited too long at the finish, wanting to go again.

About Inferno, who led with so much confidence and blind happiness. Inferno is a young dog, less than two years old, and had only led three runs before this, a truck run, a short fun run, and half of a longer training run. Seeing the photos of him coming into the finish with those floppy ears, there is a confidence in him that will be carried forward for so many years in this team. As Remy said, 'your young leader learned something, right?'

More than anyone else, this race was about Wembley. Wembley led the entire race. She knew when we were getting close to a checkpoint and would drive harder. She ate everything and was always the first one to stand up when I returned to the team after a rest. She drove like a steering wheel with every turn, and I had total faith in her. She led fearlessly through open water, glare ice, and rough terrain. She came into the finish line with the biggest grin and the tightest tug, with the same energy as how she started. She knew, the whole time, what she was doing, and as her fourth time in this race, she sure as hell did. This race, the Can Am 250, will always be Wembley's race.

So important was the superb Elissa Gramling, who coached me back onto the trail with the right mix of support and tough-headedness, offered so much laughter and cheer, and also constantly put water and food in my hands. Every time I came into the checkpoint building, or emerged from a nap, there she was, with a row of filled water bottles, and so much support and laughter. Elissa is the perfect Can Am handler. I couldn’t have done it without her.

I run these races because of so many things, to explore landscape with these amazing dogs, to be out in the wilderness, and to be on the trail with so many friends. This race is a celebration of the sport, as so many friends met us at the finish line, the volunteers and officials and almost all the mushers who had finished before me. We all stood around the team in the finish line, smiling and celebrating, the dogs smiling as well.

This was my fourth time in this race, and the third time across the finish, the third time in a row. This race was hard. But a different kind of hard compared to two years ago, to three years ago. It was the kind of hard that I knew I could wrap my arms around and lift, and I knew I could do so because of the dogs standing there with me.

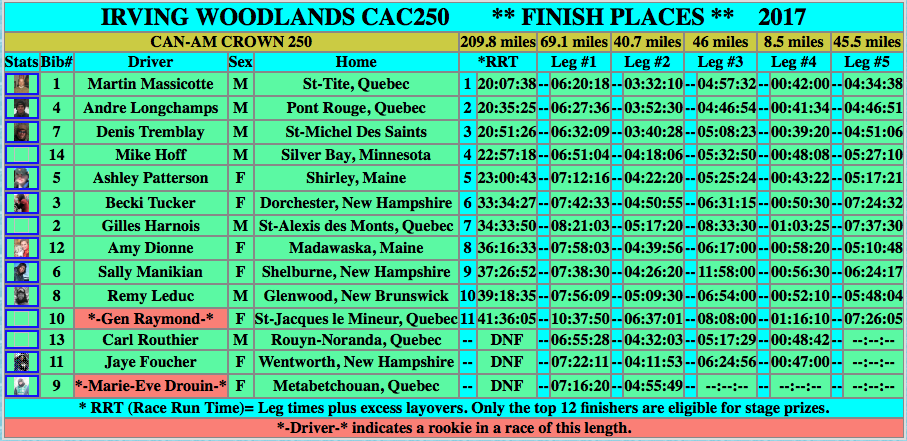

We started with 10 dogs, and finished with 7, coming in 9th place as we did two years ago.

These. Amazing. Dogs.